Most popular from web right now

The bigger the animal, the stiffer the 'shoes'

Kai-Jung Chi, an assistant professor of physics at National Chung Hsing University in Taiwan ran a series of carefully calibrated "compressive tests" on the footpads of carnivores that have that extra toe halfway up the foreleg, including dogs, wolves, domestic cats, leopards and hyenas. She was measuring the relative stiffness of the pads across species – how much they deformed under a given amount of compression.

"People hadn't looked at pads," said co-author V. Louise Roth, an associate professor of biology and evolutionary anthropology who was Chi's thesis adviser at Duke. "They've been looking at the bones and muscles, but not that soft tissue."

Whether running, walking or standing still, the bulk of the animal's weight is borne on that pillowy clover-shaped pad behind the four toes, the metapodial-phalangeal pad, or m-p pad for short. It's made from pockets of fatty tissue hemmed in by baffles of collagen. Chi carefully dissected these pads whole from the feet of deceased animals (none of which were euthanized for this study), so that they could be put in the strain meter by themselves without any surrounding structures.

Laid out on a graph, Chi's analysis of 47 carnivore species shows that the area of their m-p pads doesn't increase at the same rate as the body sizes. But the stiffness of pads does increase with size, and that's what keeps the larger animal's feet from being unwieldy.

The mass of the animal increases cubically with its greater size, but the feet don't scale up the same way. "A mouse and an elephant are made with the same ingredients," Roth said. "So how do you do that?"

Earlier research had found that the stresses on the long bones of the limbs stay fairly consistent over the range of sizes, in part because of changes in posture that distribute the stresses of walking differently, Roth said. But that clearly wasn't enough by itself.

The researchers also found that larger animals have a pronounced difference in stiffness between the pads on the forelimbs and the pads on the hind limbs. Bigger animals have relatively softer pads on their rear feet, whereas in smaller animals the front and rear are about the same stiffness.

Chi thinks the softer pads on the rear of the bigger animals may help them recover some energy from each step, and provide a bit more boost to their propulsion. (Think of the way a large predator folds up its forelimbs and launches itself with its hind legs.)

"It is as if the foot pads' stiffness is tuned to enhance how the animal moves and how strength is maintained in its bones," Roth said.

The research appears today in the Journal of the Royal Society, Interface. It was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Chi has new work under way that looks at the construction of the human heel in the same ways.

Friday, February 26, 2010 | 0 Comments

Small dogs originated in the Middle East

Reduction in body size is a common feature of domestication and has been seen in other domesticated animals including cattle, pigs and goats. According to Gray, "Small size could have been more desirable in more densely packed agricultural societies, in which dogs may have lived partly indoors or in confined outdoor spaces".

Thursday, February 25, 2010 | 0 Comments

New dinosaur discovered head first, for a change

Britt is a co-author on the discovery paper scheduled to appear in the journal Naturwissenshaften.

The lead author is Daniel Chure, a paleontologist at Dinosaur National Monument, who has no trouble boiling down the significance of the discovery.

"We've got skulls!" he shouted with sweeping hand gestures during a recent visit to the site.

BYU geology students and faculty resorted to jackhammers and concrete saws to cut through the hardened 105-million-year-old sandstone containing the bones. At one point the National Park Service called in a crew to blast away the overlying rock with explosives.

The skulls are temporarily on display at BYU's Museum of Paleontology, where visitors can also watch BYU students prepare other bones from Abydosaurus.

"The hardest bone I personally have worked on is a vertebra that was half-eroded before discovery and is so fragile that it crumbles if you look at it wrong," said Kimmy Hales, a geology major studying vertebrate paleontology at BYU. "The funnest project I have worked on was a set of five toe bones. Each toe bone was larger than my hand."

Analysis of the bones indicates that the closest relative of Abydosaurus is Brachiosaurus, which lived 45 million years earlier. The four Abydosaurus specimens were all juveniles.

Most of what scientists know about sauropods is from the neck down, but the skulls from Abydosaurus give a few clues about how the largest land animals to roam the earth ate their food.

"They didn't chew their food; they just grabbed it and swallowed it," Britt said. "The skulls are only one two-hundredth of total body volume and don't have an elaborate chewing system."

All sauropods ate plants and continually replaced their teeth throughout their lives. In the Jurassic Period, sauropods exhibited a wide range of tooth shapes. But by the end of the dinosaur age, all sauropods had narrow, pencil-like teeth.

Abydosaurus teeth are somewhere in between, reflecting a trend toward smaller teeth and more rapid tooth replacement.

The fossils were excavated from the Cedar Mountain Formation in Dinosaur National Monument near Vernal, Utah. The site is just a quarter of a mile away from the condemned visitor center that displays thousands of bones that remain in place on an uplifted slab of sandstone.

University of Michigan researchers John Whitlock and Jeffrey Wilson are also co-authors on the study.

What's in the name Abydosaurus mcintoshi?

The generic name refers to Abydos, the Greek name for the city along the Nile River (now El Araba el Madfuna) that was the burial place of the head and neck of Osiris, Egyptian god of life, death and fertility. Abydos alludes to the type specimen, which is a skull and neck found in a quarry overlooking the Green River. Sauros is the Greek word for lizard.

The specific name mcintoshi honors the American paleontologist Jack McIntosh for his contributions to the study of sauropod dinosaurs. In 1975 McIntosh debunked the myth of Brontosaurus, exposing it as a mixed-up skeleton with an Apatosaurus body and a Camarasaurus skull.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010 | 0 Comments

DNA evidence tells 'global story' of human history

The course and the extent of these first migrations remains evident in the genetic makeup of humans living today, but later migrations and the cultural practices that people carried with them—farming in particular—have also left their legacy. That legacy looks remarkably similar wherever farming spread, in Europe, Africa, and East Asia. Natural selection also left its mark: A review by Jonathan Pritchard of the University of Chicago examines evidence for the genetic basis of human adaptations and the extent to which differences among human populations in characteristics such as lactose tolerance have been selected for over evolutionary time.

Each of the reviews is packed with fascinating insights. For instance, a review by Mark Stoneking and Frederick Delfin at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology tells of an early migration of modern humans from Africa along a southern route to East Asia. Europe is perhaps the best-studied continent in terms of archaeogenetics, writes Martin Richards of the University of Leeds and his colleagues, and includes what Richards refers to as five major episodes, including the repopulation of Northern Europe after the Late Glacial Maximum. In the case of the Americas, DNA evidence has confirmed the Asian origin of indigenous Americans and more precise estimates of when Native Americans emerged. Dennis O'Rourke and Jennifer Raff of the University of Utah note, however, that many questions about the date of the initial colonization of the Americas remain.

Overall, the reviews show just how clear it has become that all of us trace our evolutionary roots to Africa, Renfrew says. For most of history, humans were not evolving in isolation on separate continents. When it comes to our more recent history, stay tuned: Many surprising discoveries are likely in store over the next 20 years.

Of course, there are many things about our ancient ancestors we will never be able to know with any certainty, Partha Majumder of the Indian Statistical Institute reminds us in his review of human genetic history in South Asia.

"About a thousand years ago, a small group of anatomically modern humans migrated out of Africa," he writes. "We will never know for sure which causes initiated this migration… The process continued for thousands of years; today humans occupy the entire world."

Tuesday, February 23, 2010 | 0 Comments

New study finds link between marine algae and whale diversity over time

"This study shows that if we look at the bottom of the food chain, it might tell you something about the top," says Uhen. "Diatoms are key primary producers in the modern ocean, and thus help to form the base of the marine food chain. The fossil record clearly shows that diatoms and whales rose and fell in diversity together during the last 30 million years."

Uhen says this is the first time that such a correlation has been shown. Though scientists in the past have tried to answer the question of how the modern diversity of whale and dolphins arise, this question has been difficult to answer. The fossil record might not truly reflect evolutionary history, says Uhen. "Is it possible that the diversity of fossils we find through geological time might really just reflect the amount of preserved sedimentary rock paleontologists can search – the more rock there is, the more fossils we find? This comprehensive study has shown that the diversity of these fossils is in fact not driven by the sedimentary rock record."

The researchers hope these findings will encourage other specialists to look at other animals with a similar narrow ecology to see if this link translates.

Uhen is a term assistant professor in Mason's Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Earth Sciences and is an expert in marine mammal fossils. In the future, he hopes to conduct research on how the body size of whales changes over time, and how whales became the largest living organisms in the world.

Monday, February 22, 2010 | 0 Comments

Pitt-led study debunks millennia-old claims of systematic infant sacrifice in ancient Carthage

Schwartz worked with Frank Houghton of the Veterans Research Foundation of Pittsburgh, Roberto Macchiarelli of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and Luca Bondioli of the National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome to inspect the remains of children found in Tophets, burial sites peripheral to conventional Carthaginian cemeteries for older children and adults. Tophets housed urns containing the cremated remains of young children and animals, which led to the theory that they were reserved for victims of sacrifice.

Schwartz and his coauthors tested the all-sacrifice claim by examining the skeletal remains from 348 urns for developmental markers that would determine the children's age at death. Schwartz and Houghton recorded skull, hip, long bone, and tooth measurements that indicated most of the children died in their first year with a sizeable number aged only two to five months, and that at least 20 percent of the sample was prenatal.

Schwartz and Houghton then selected teeth from 50 individuals they concluded had died before or shortly after birth and sent them to Macchiarelli and Bondioli, who examined the samples for a neonatal line. This opaque band forms in human teeth between the interruption of enamel production at birth and its resumption within two weeks of life. Identification of this line is commonly used to determine an infant's age at death. Macchiarelli and Bondioli found a neonatal line in the teeth of 24 individuals, meaning that the remaining 26 individuals died prenatally or within two weeks of birth, the researchers reported.

The contents of the urns also dispel the possibility of mass infant sacrifice, Schwartz and Houghton noted. No urn contained enough skeletal material to suggest the presence of more than two complete individuals. Although many urns contained some superfluous fragments belonging to additional children, the researchers concluded that these bones remained from previous cremations and may have inadvertently been mixed with the ashes of subsequent cremations.

The team's report also disputes the contention that Carthaginians specifically sacrificed first-born males. Schwartz and Houghton determined sex by measuring the sciatic notch—a crevice at the rear of the pelvis that's wider in females—of 70 hipbones. They discovered that 38 pelvises came from females and 26 from males. Two others were likely female, one likely male, and three undetermined.

Schwartz and his colleagues conclude that the high incidence of prenate and infant mortality are consistent with modern data on stillbirths, miscarriages, and infant death. They write that if conditions in other ancient cities held in Carthage, young and unborn children could have easily succumbed to the diseases and sanitary shortcomings found in such cities as Rome and Pompeii.

Friday, February 19, 2010 | 0 Comments

The putative skull of St. Bridget can be questioned

The scientists analysed small pieces of the skulls and concluded that both skulls are female by a nuclear DNA-analysis. Moreover, a maternal relationship can be excluded by analysis of mitochondrial DNA. There were indications of a difference in the preservation of the DNA, which could be due to an age difference between the skulls. Therefore, Professor Göran Possnert at Uppsala University's Tandem Laboratory performed further testing, using advanced radiocarbon dating (C-14) technology. The results confirmed those obtained by the DNA analysis.

"One skull cannot be attributed to Bridget or Catherine as it dates back to the period 1470-1670. The other skull, thought to be from Saint Bridget, is dated to 1215-1270 and is thus not likely to be from the 14th Century when Bridget lived. It cannot, however, be completely excluded that the older skull is from Bridget if she had a diet dominated by fish, which can shift the dating results. But this is unlikely," says Göran Possnert.

"The results from both methods support each other. Our DNA analyses show that we can exclude a mother and daughter relationship. This is also confirmed by the dating as a difference of at least 200 years between the skulls is seen," says Marie Allen.

Thursday, February 18, 2010 | 0 Comments

King Tut's death explained?

Zahi Hawass, Ph.D., of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt, and colleagues conducted a study to determine familial relationships among 11 royal mummies of the New Kingdom, and to search for pathological features attributable to inherited disorders, infectious diseases and blood relationship. They also examined for evidence regarding Tutankhamun's death, with some scholars having hypothesized that it was attributable to an injury; septicemia (bloodstream infection) or fat embolism (release of fat into an artery) secondary to a femur fracture; murder by a blow to the back of the head; or poisoning.

From September 2007 to October 2009, royal mummies underwent detailed anthropological, radiological, and genetic studies (DNA was extracted from 2 to 4 different biopsies per mummy). In addition to Tutankhamun, 10 mummies (circa 1410-1324 B.C.) possibly or definitely closely related in some way to Tutankhamun were chosen; of these, the identities were certain for only 3. In addition to these 11 mummies, 5 other royal individuals dating to the early New Kingdom (circa 1550-1479 B.C.) were selected that were distinct from the supposed members of the Tutankhamun lineage. Most of these 5 mummies were used as a morphological (form and structure) and genetic control group. Genetic fingerprinting allowed the construction of a 5-generation pedigree of Tutankhamun's immediate lineage.

The researchers found that several of the anonymous mummies or those with suspected identities were now able to be addressed by name, which included KV35EL, who is Tiye, mother of the pharaoh Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun, and the KV55 mummy, who is most probably Akhenaten, father of Tutankhamun. This kinship is supported in that several unique anthropological features are shared by the 2 mummies and that the blood group of both individuals is identical. The researchers identified the KV35YL mummy as likely Tutankhamun's mother.

No signs of gynecomastia or Marfan syndrome were found. "Therefore, the particular artistic presentation of persons in the Amarna period is confirmed as a royally decreed style most probably related to the religious reforms of Akhenaten. It is unlikely that either Tutankhamun or Akhenaten actually displayed a significantly bizarre or feminine physique. It is important to note that ancient Egyptian kings typically had themselves and their families represented in an idealized fashion," they write.

The researchers did find an accumulation of malformations in Tutankhamun's family. "Several pathologies including Kohler disease II [bone disorder] were diagnosed in Tutankhamun; none alone would have caused death. Genetic testing for STEVOR, AMA1, or MSP1 genes specific for Plasmodium falciparum [the malaria parasite] revealed indications of malaria tropica in 4 mummies, including Tutankhamun's. These results suggest avascular bone necrosis [condition in which the poor blood supply to the bone leads to weakening or destruction of an area of bone] in conjunction with the malarial infection as the most likely cause of death in Tutankhamun. Walking impairment and malarial disease sustained by Tutankhamun is supported by the discovery of canes and an afterlife pharmacy in his tomb," the authors write. They add that a sudden leg fracture, possibly from a fall, might have resulted in a life-threatening condition when a malaria infection occurred.

"In conclusion, this study suggests a new approach to research into the molecular genealogy and pathogen paleogenomics of the Pharaonic era. With additional data, a scientific discipline called molecular Egyptology might be established and consolidated, thereby merging natural sciences, life sciences, cultural sciences, humanities, medicine, and other fields."

Wednesday, February 17, 2010 | 0 Comments

Meteorite That Fell in 1969 Still Revealing Secrets of the Early Solar System

A new analysis of the Murchison meteorite, which fell to Earth more than 40 years ago, reveals tens of thousands of organic compounds.

A new analysis of the Murchison meteorite, which fell to Earth more than 40 years ago, reveals tens of thousands of organic compounds.Tuesday, February 16, 2010 | 0 Comments

On Crete, New Evidence of Very Ancient Mariners

Crete has been an island for more than five million years, meaning that the toolmakers must have arrived by boat. So this seems to push the history of Mediterranean voyaging back more than 100,000 years, specialists in Stone Age archaeology say. Previous artifact discoveries had shown people reaching Cyprus, a few other Greek islands and possibly Sardinia no earlier than 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

The oldest established early marine travel anywhere was the sea-crossing migration of anatomically modern Homo sapiens to Australia, beginning about 60,000 years ago. There is also a suggestive trickle of evidence, notably the skeletons and artifacts on the Indonesian island of Flores, of more ancient hominids making their way by water to new habitats.

Even more intriguing, the archaeologists who found the tools on Crete noted that the style of the hand axes suggested that they could be up to 700,000 years old. That may be a stretch, they conceded, but the tools resemble artifacts from the stone technology known as Acheulean, which originated with prehuman populations in Africa.

More than 2,000 stone artifacts, including the hand axes, were collected on the southwestern shore of Crete, near the town of Plakias, by a team led by Thomas F. Strasser and Eleni Panagopoulou. She is with the Greek Ministry of Culture and he is an associate professor of art history at Providence College in Rhode Island. They were assisted by Greek and American geologists and archaeologists, including Curtis Runnels of Boston University.

Dr. Strasser described the discovery last month at a meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. A formal report has been accepted for publication in Hesparia, the journal of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, a supporter of the fieldwork.

The Plakias survey team went in looking for material remains of more recent artisans, nothing older than 11,000 years. Such artifacts would have been blades, spear points and arrowheads typical of Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.

“We found those, then we found the hand axes,” Dr. Strasser said last week in an interview, and that sent the team into deeper time.

“We were flummoxed,” Dr. Runnels said in an interview. “These things were just not supposed to be there.”

Word of the find is circulating among the ranks of Stone Age scholars. The few who have seen the data and some pictures — most of the tools reside in Athens — said they were excited and cautiously impressed. The research, if confirmed by further study, scrambles timetables of technological development and textbook accounts of human and prehuman mobility.

Ofer Bar-Yosef, an authority on Stone Age archaeology at Harvard, said the significance of the find would depend on the dating of the site. “Once the investigators provide the dates,” he said in an e-mail message, “we will have a better understanding of the importance of the discovery.”

Dr. Bar-Yosef said he had seen only a few photographs of the Cretan tools. The forms can only indicate a possible age, he said, but “handling the artifacts may provide a different impression.” And dating, he said, would tell the tale.

Dr. Runnels, who has 30 years’ experience in Stone Age research, said that an analysis by him and three geologists “left not much doubt of the age of the site, and the tools must be even older.”

The cliffs and caves above the shore, the researchers said, have been uplifted by tectonic forces where the African plate goes under and pushes up the European plate. The exposed uplifted layers represent the sequence of geologic periods that have been well studied and dated, in some cases correlated to established dates of glacial and interglacial periods of the most recent ice age. In addition, the team analyzed the layer bearing the tools and determined that the soil had been on the surface 130,000 to 190,000 years ago.

Dr. Runnels said he considered this a minimum age for the tools themselves. They include not only quartz hand axes, but also cleavers and scrapers, all of which are in the Acheulean style. The tools could have been made millenniums before they became, as it were, frozen in time in the Cretan cliffs, the archaeologists said.

Dr. Runnels suggested that the tools could be at least twice as old as the geologic layers. Dr. Strasser said they could be as much as 700,000 years old. Further explorations are planned this summer.

The 130,000-year date would put the discovery in a time when Homo sapiens had already evolved in Africa, sometime after 200,000 years ago. Their presence in Europe did not become apparent until about 50,000 years ago.

Archaeologists can only speculate about who the toolmakers were. One hundred and thirty thousand years ago, modern humans shared the world with other hominids, like Neanderthals and Homo heidelbergensis. The Acheulean culture is thought to have started with Homo erectus.

The standard hypothesis had been that Acheulean toolmakers reached Europe and Asia via the Middle East, passing mainly through what is now Turkey into the Balkans. The new finds suggest that their dispersals were not confined to land routes. They may lend credibility to proposals of migrations from Africa across the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain. Crete’s southern shore where the tools were found is 200 miles from North Africa.

“We can’t say the toolmakers came 200 miles from Libya,” Dr. Strasser said. “If you’re on a raft, that’s a long voyage, but they might have come from the European mainland by way of shorter crossings through Greek islands.”

But archaeologists and experts on early nautical history said the discovery appeared to show that these surprisingly ancient mariners had craft sturdier and more reliable than rafts. They also must have had the cognitive ability to conceive and carry out repeated water crossing over great distances in order to establish sustainable populations producing an abundance of stone artifacts.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010 | 0 Comments

Chemical analyses uncover secrets of an ancient amphora

A team of chemists from the University of Valencia (UV) has confirmed that the substance used to hermetically seal an amphora found among remains at Lixus, in Morocco, was pine resin. The scientists also studied the metallic fragments inside the 2,000-year-old vessel, which could be fragments of material used for iron-working. In 2005, a group of archaeologists from the UV discovered a sealed amphora among the remains at Lixus, an ancient settlement founded by the Phoenicians near Larache, in Morocco. Since then, researchers from the Department of Analytical Chemistry at this university have been carrying out various studies into it components.

A team of chemists from the University of Valencia (UV) has confirmed that the substance used to hermetically seal an amphora found among remains at Lixus, in Morocco, was pine resin. The scientists also studied the metallic fragments inside the 2,000-year-old vessel, which could be fragments of material used for iron-working. In 2005, a group of archaeologists from the UV discovered a sealed amphora among the remains at Lixus, an ancient settlement founded by the Phoenicians near Larache, in Morocco. Since then, researchers from the Department of Analytical Chemistry at this university have been carrying out various studies into it components."We have studied the substance that was used to seal the container using three different techniques, and we compared it with pine resin from today", José Vicente Gimeno, one of the authors of the study and a senior professor at the UV, tells SINC.

The results confirm that the small sample analysed, which is 2,000 years old, contains therpenic organic compounds (primaric, isoprimaric and dehydroabietic acids), allowing this to be classified as resin from a tree from the Pinus genus.

The researchers have identified some substances that indicate the age of resins, such as such as 7-oxo-DHA acid, although this kind of compound was not abundant in the sample due to the amphora's good state of preservation. In addition, Gimeno says that the archaeological resin of the amphora found was hard and blackish with yellow spots, unlike present-day resin, which is more malleable and orangey in colour, similar to the fresh sap of the tree.

Italic amphora in the Straits of Gibraltar

"The jar was found in an area that must have been the amphora store of a house from the period between 50 BCE and 10 CE", Carmen Aranegui, coordinator of the excavations at Lixus and also a senior professor at the UV, tells SINC.

The archaeologist, who has been working at the site for the past 15 years with the Institut National des Sciences de l'Archéologie et du Patrimoine of Rabat, says the amphora is Italic, probably from the region of Campania. It is currently being housed in the archaeological warehouse at Larache. These jars were used as containers for wine or salted products, but after serving this purpose they could be re-used as watertight storage containers. The amphora found contains metallic fragments, and the scientists have analysed these too.

According to the experts, it is likely that this vessel was undergoing a second use, protecting pieces of iron from corrosion, so that they could later be used in the iron-forging process in a local foundry at the time.

Not far from this amphora, another has been found at Lixus bearing the mark in Latin 'A.MISE', which is the name of the person who made the jar, and has also been found on another similar one found in Cadiz, Spain. "This was a period when there was great contact between these two cities on either side of the Straits of Gibraltar", points out Aranegui.

Monday, February 15, 2010 | 0 Comments

Queen's helps produce archaeological 'time machine'

Researchers at Queen's University have helped produce a new archaeological tool which could answer key questions in human evolution. The new calibration curve, which extends back 50,000 years is a major landmark in radiocarbon dating-- the method used by archaeologists and geoscientists to establish the age of carbon-based materials.

Researchers at Queen's University have helped produce a new archaeological tool which could answer key questions in human evolution. The new calibration curve, which extends back 50,000 years is a major landmark in radiocarbon dating-- the method used by archaeologists and geoscientists to establish the age of carbon-based materials.The project was led by Queen's University Belfast through a National Environment Research Centre (NERC) funded research grant to Dr Paula Reimer and Professor Gerry McCormac from the Centre for Climate, the Environment and Chronology (14CHRONO) at Queen's and statisticians at the University of Sheffield.

Ron Reimer and Professor Emeritus Mike Baillie from Queen's School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology also contributed to the work.

The curve called INTCAL09, has just been published in the journal Radiocarbon. It not only extends radiocarbon calibration but also considerably improves earlier parts of the curve.

Dr Reimer said: "The new radiocarbon calibration curve will be used worldwide by archaeologists and earth scientists to convert radiocarbon ages into a meaningful time scale comparable to historical dates or other estimates of calendar age.

"It is significant because this agreed calibration curve now extends over the entire normal range of radiocarbon dating, up to 50,000 years before today. Comparisons of the new curve to ice-core or other climate archives will provide information about changes in solar activity and ocean circulation."

It has taken nearly 30 years for researchers to produce a calibration curve this far back in time.

Since the early 1980s, an international working group called INTCAL has been working on the project.

The principle of radiocarbon dating is that plants and animals absorb trace amounts of radioactive carbon-14 from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere while they are alive but stop doing so when they die. The carbon-14 decays from archaeological and geological samples so the amount left in the sample gives an indication of how old the sample is.

As the amount of carbon -14 in the atmosphere is not constant, but varies with the strength of the earth's magnetic field, solar activity and ocean radiocarbon ages must be corrected with a calibration curve.

Most experts consider the technical limit of radiocarbon dating to be about 50,000 years, after which there is too little carbon-14 left to measure accurately with present day technology.

Friday, February 12, 2010 | 0 Comments

Byzantine-era street found in Jerusalem

With the help of an ancient mosaic map, Israeli archaeologists said Wednesday they have unearthed a section of an old stone-flagged street in Jerusalem that provides important new evidence about the city's commercial life 1,500 years ago.

With the help of an ancient mosaic map, Israeli archaeologists said Wednesday they have unearthed a section of an old stone-flagged street in Jerusalem that provides important new evidence about the city's commercial life 1,500 years ago.The discovery conforms to the layout of the city depicted in a famous 6th-century mosaic map discovered more than 100 years ago in a Jordanian church, said excavation director Ofer Sion.

The map has long been used as a guide to understanding the shape of the city from the 4th to 6th centuries, and the direction of the street is new evidence the map is correct, he said.

Jerusalem during this time had become a Roman city named Aelia Capitolina, with Jews barred from entering after their revolt against their Roman overlords in 132 A.D. It became a major center for the emerging Christian religion.

The Byzantine Empire evolved out of the eastern half of the Roman Empire when the western part succumbed to barbarian invasions and ruled over much of the Middle East until the Arab conquests of the 7th century.

A staunchly Christian empire based in Constantinople, now Istanbul, it valued Jerusalem as a key Christian religious center and invested heavily into the city, which became a destination for thousands of pilgrims every year.

"This street was the center during the most (commercially) successful period in the history of (ancient) Jerusalem," Sion said. "It is wonderful that (today's street) actually preserved the route of the noisy street from 1,500 years ago."

Working from the historic map, archaeologists three months ago uncovered the section of the wide, white stone street 14 feet (4.5 meters) below the current street level.

Archaeologists have already excavated another ancient street in Jerusalem from that time known as the Cardo, which ran north to south and hosted many shops along its pillared length. Sion said the newly found street included a sidewalk and row of columns.

The map, uncovered in 1894 on the floor of a Byzantine-era church in Madaba, Jordan, shows the locations of major streets and the Christian sites in the city, including the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the site where the faithful believe Jesus was crucified, buried and resurrected.

Once restoration work is completed, within the next few weeks, the segment of street will be covered because of heavy pedestrian traffic, Sion said. It has yet to be decided if the site will be available for viewing.

The Israel Antiquities Authority undertook the project in response to a municipal plan to build an electric cable system on the site. In a land where every shovel might unearth something ancient, Israeli law requires the authority to inspect construction zones for ruins before work begins.

Thursday, February 11, 2010 | 0 Comments

What was that? Unraveling a 400-million-year-old mystery

Graham and her colleagues hypothesized that Prototaxites fossils may be composed of partially degraded wind-, gravity-, or water-rolled mats of mixotrophic (capable of deriving energy from multiple sources) liverworts that are associated with fungi and cyanobacteria. This situation resembles the mats produced by the modern liverwort genus Marchantia. The authors tested their hypothesis by treating Marchantia polymorpha in a manner to reflect the volcanically-influenced, warm environments typical of the Devonian period and compared the resulting remains to Prototaxites fossils. Graham and her colleagues investigated the mixotrophic ability of M. polymorpha by assessing whether M. polymorpha grown in a glucose-based medium is capable of acquiring carbon from its substrate.

"For our structural comparative work," Graham said, "we were extremely fortunate to have an amazing thin slice of the rocky fossil, made in 1954 by the eminent paleobotanist Chester A. Arnold."

Their structural and physiological studies showed that the fossil Prototaxites and the modern liverwort Marchantia have many similarities in their external structure, internal anatomy, and nutrition. Despite being subjected to conditions that would promote decomposition and desiccation, the rhizoids of M. polymorpha survived degradation, and with the mat rolled, created the appearance of concentric circles. The fungal hyphae associated with living liverworts also survived treatment, suggesting that the branched tubes in fossils may be fungal hyphae. The very narrow tubes in the fossils resemble filamentous cyanobacteria that the researchers found wrapped around the rhizoids of the decaying M. polymorpha.

"We were really excited when we saw how similar the ultrastructure of our liverwort rhizoid walls was to images of Prototaxites tubes published in 1976 by Rudy Schmid," Graham said.

In their investigations into the nutritional requirements of M. polymorpha, Graham and her colleagues found that the growth of M. polymorpha in a glucose-based medium was approximately 13 times that seen when the liverwort was grown in a medium without glucose. Stable carbon isotope analyses indicated that less than 20% of the carbon in the glucose-grown liverwort came from the atmosphere. The stable carbon isotope values obtained from M. polymorpha grown with varying amounts of cyanobacteria present span the range of values reported for Prototaxites fossils. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the liverworts have a capacity for mixotrophic nutrition when glucose is present and that mixotrophy and/or the presence of cyanobacteria could be responsible for the stable carbon isotope values obtained from Prototaxites.

Graham and her colleagues' results demonstrate that liverworts were important components of Devonian ecosystems. Their results support previous hypotheses that microbial associations and mixotrophy are ancient plant traits, rather than ones that have evolved recently.

Thursday, February 11, 2010 | 0 Comments

Why Did Mammals Survive the 'K/T Extinction'?

Picture a dinosaur. Huge, menacing creatures, they ruled the Earth for nearly 200 million years, striking fear with every ground-shaking stride. Yet these great beasts were no match for a 6-mile wide meteor that struck near modern-day Mexico 65 million years ago, incinerating everything in its path. This catastrophic impact -- called the Cretaceous-Tertiary or K/T extinction event -- spelled doom for the dinosaurs and many other species. Some animals, however, including many small mammals, managed to survive.

Picture a dinosaur. Huge, menacing creatures, they ruled the Earth for nearly 200 million years, striking fear with every ground-shaking stride. Yet these great beasts were no match for a 6-mile wide meteor that struck near modern-day Mexico 65 million years ago, incinerating everything in its path. This catastrophic impact -- called the Cretaceous-Tertiary or K/T extinction event -- spelled doom for the dinosaurs and many other species. Some animals, however, including many small mammals, managed to survive."They were better at escaping the heat," said Russ Graham, senior research associate in geosciences at Penn State. "It was the huge amount of thermal heat released by the meteor strike that was the main cause of the K/T extinction."

He said underground burrows and aquatic environments protected small mammals from the brief but drastic rise in temperature. In contrast, the larger dinosaurs would have been completely exposed, and vast numbers would have been instantly burned to death.

After several days of searing heat, the earth's surface temperature returned to bearable levels, and the mammals emerged from their burrows, but it was a barren wasteland they encountered, one that presented yet another set of daunting conditions to be overcome, Graham said. It was their diet which enabled these mammals to survive in habitats nearly devoid of plant life.

"Even if large herbivorous dinosaurs had managed to survive the initial meteor strike, they would have had nothing to eat," he said, "because most of the earth's above-ground plant material had been destroyed."

Mammals, in contrast, could eat insects and aquatic plants, which were relatively abundant after the meteor strike. As the remaining dinosaurs died off, mammals began to flourish. Although representatives from other classes of animals also survived the K/T extinction -- crocodiles, for instance, had the saving ability to take to water -- mammals were clearly the main beneficiaries and they have since spread to nearly every corner of the planet.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010 | 0 Comments

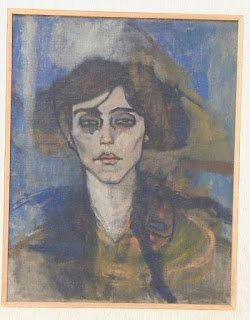

Has the mystery of the Portrait of Maud Abrantes been solved?

A century after Amedeo Modigliani painted the Portrait of Maud Abrantes, the mystery behind the painting might be solved. Ofra Rimon, Director and Curator of the Hecht Museum at the University of Haifa, discovered that hidden in the painting is the portrait of another woman. "Modigliani was probably not happy with that painting and decided to paint over it in favor of a portrait of Maud," she claims. In 1908 Modigliani painted the Portrait of Maud Abrantes on the same canvas as he had painted Nude with a Hat earlier that year. Like many painters with limited means during that period, he turned the canvas over to use the other side. But unlike common practice, he also turned it upside down. Even though this was such an irregular act, and despite the fact that the two paintings are central to most Modigliani exhibitions over recent years, art researchers have not given their attention to this oddity.

A century after Amedeo Modigliani painted the Portrait of Maud Abrantes, the mystery behind the painting might be solved. Ofra Rimon, Director and Curator of the Hecht Museum at the University of Haifa, discovered that hidden in the painting is the portrait of another woman. "Modigliani was probably not happy with that painting and decided to paint over it in favor of a portrait of Maud," she claims. In 1908 Modigliani painted the Portrait of Maud Abrantes on the same canvas as he had painted Nude with a Hat earlier that year. Like many painters with limited means during that period, he turned the canvas over to use the other side. But unlike common practice, he also turned it upside down. Even though this was such an irregular act, and despite the fact that the two paintings are central to most Modigliani exhibitions over recent years, art researchers have not given their attention to this oddity.As Rimon showed this unique work to guests at the Hecht Museum, she suddenly noticed another woman: In the area of Maud's neck and chest a sharp eye can make out the outline of the face of a woman in a hat.

"For years I have passed by the painting almost every day and have stood in front of it providing countless explanations. But I never noticed anything irregular about the portrait, and have only been frustrated by Modigliani's disregard for onlookers who are made to view one of the paintings upside down. Then, just out of the blue, when I was escorting guests in the art wing and drew their attention to this fantastic Modigliani piece, the mystery was solved. In my excitement, I shrieked, 'Here's the answer! The mystery is solved! There is another portrait beneath Maud's and this one is facing the other direction to Maud.' The eyes, facial outline and hat can be discerned. It turns out that Modigliani painted the portrait of this mysterious and hidden woman before painting the portrait of Maud Abrantes. He decided not to keep the first painting and blurred it with brushes of color. But that did not suffice: he also turned the canvas over and began to paint anew on the clean part of the canvas," she explained.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010 | 0 Comments

New theory on the origin of primates

In this new approach to molecular phylogenetics, vicariance, and plate tectonics, Heads shows that the distribution ranges of primates and their nearest relatives, the tree shrews and the flying lemurs, conforms to a pattern that would be expected from their having evolved from a widespread ancestor. This ancestor could have evolved into the extinct Plesiadapiformes in north America and Eurasia, the primates in central-South America, Africa, India and south East Asia, and the tree shrews and flying lemurs in South East Asia.

Divergence between strepsirrhines (lemurs and lorises) and haplorhines (tarsiers and anthropoids) is correlated with intense volcanic activity on the Lebombo Monocline in Africa about 180 million years ago. The lemurs of Madagascar diverged from their African relatives with the opening of the Mozambique Channel (160 million years ago), while New and Old World monkeys diverged with the opening of the Atlantic about 120 million years ago.

"This model avoids the confusion created by the center of origin theories and the assumption of a recent origin for major primate groups due to a misrepresentation of the fossil record and molecular clock divergence estimates" said Michael from his New Zealand office. "These models have resulted in all sorts of contradictory centers of origin and imaginary migrations for primates that are biogeographically unnecessary and incompatible with ecological evidence".

The tectonic model also addresses the otherwise insoluble problem of dispersal theories that enable primates to cross the Atlantic to America, and the Mozambique Channel to Madagascar although they have not been able to cross 25 km from Sulawesi to Moluccan islands and from there travel to New Guinea and Australia.

Heads acknowledged that the phylogenetic relationships of some groups such as tarsiers, are controversial, but the various alternatives do not obscure the patterns of diversity and distribution identified in this study.

Biogeographic evidence for the Jurassic origin for primates, and the pre-Cretaceous origin of major primate groups considerably extends their divergence before the fossil record, but Heads notes that fossils only provide minimal dates for the existence of particular groups, and there are many examples of the fossil record being extended for tens of millions of years through new fossil discoveries.

The article notes that increasing numbers of primatologists and paleontologists recognize that the fossil record cannot be used to impose strict limits on primate origins, and that some molecular clock estimates also predict divergence dates pre-dating the earliest fossils. These considerations indicate that there is no necessary objection to the biogeographic evidence for divergence of primates beginning in the Jurassic with the origin of all major groups being correlated with plate tectonics.

Tuesday, February 09, 2010 | 0 Comments

Ancient remains put teeth into Barker hypothesis

"Teeth are like a snapshot into the past," Armelagos says. "Since the chronology of enamel development is well known, it's possible to determine the age at which a physiological disruption occurred. The evidence is there, and it's indisputable."

The Barker hypothesis is named after epidemiologist David Barker, who during the 1980s began studying links between early infant health and later adult health. The theory, also known as the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease Hypothesis (DOHaD), has expanded into wide acceptance.

As one of the founders of the field of bioarcheology, Armelagos studies skeletal remains to understand how diet and disease affected populations. Tooth enamel can give a particularly telling portrait of physiological events, since the enamel is secreted in a regular, ring-like fashion, starting from the second trimester of fetal development. Disruptions in the formation of the enamel, which can be caused by disease, poor diet or psychological stress, show up as grooves on the tooth surface.

Armelagos and other bioarcheologists have noted the connection between dental enamel and early mortality for years. For the Evolutionary Biology paper, Armelagos led a review of the evidence from eight published studies, applying the lens of the Barker hypothesis to remains dating back as far as 1 million years.

One study of a group of Australopithecines from the South African Pleistocence showed a nearly 12-year decrease in mean life expectancy associated with early enamel defects. In another striking example, remains from Dickson Mounds, Illinois, showed that individuals with teeth marked by early life stress lived 15.4 years less than those without the defects.

"During prehistory, the stresses of infectious disease, poor nutrition and psychological trauma were likely extreme. The teeth show the impact," Armelagos says.

Until now, teeth have not been analyzed using the Barker hypothesis, which has mainly been supported by a correlation between birth weight in modern-day, high-income populations and ailments like diabetes and heart disease.

"The prehistoric data suggests that this type of dental evidence could be applied in modern populations, to give new insights into the scope of the Barker hypothesis," Armelagos says. "Bioarcheology is yielding lessons that are still relevant today in the many parts of the world in which infectious diseases and under-nutrition are major killers."

Monday, February 08, 2010 | 0 Comments

Yale scientists complete color palette of a dinosaur for the first time

"This was no crow or sparrow, but a creature with a very notable plumage," said Richard O. Prum, chair and the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale and a co-author of the study. "This would be a very striking animal if it was alive today."

The color patterns of the limbs, which strongly resemble those sported by modern day Spangled Hamburg chickens, probably functioned in communication and may have helped the dinosaur to attract mates, suggested Prum.

The transformation of mankind's view of dinosaurs from dull to flamboyant was made possible by a discovery by Yale graduate student Jakob Vinther in the Department of Geology and Geophysics. Vinther was studying the ink sac of an ancient squid and realized that microscopic granular-like features within the fossil were actually melanosomes – a cellular organelle that contains melanin, a light-absorbing pigment in animals, including birds.

While some scientists thought these granules were remnants of ancient bacteria, Vinther, Prum and Derek E.G. Briggs, the Frederick William Beinecke Professor of Geology and Geophysics and director of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, disagreed. First, they tested Vinther's theory on a 112 million year old feather from Brazil and later inferred the colors of an extinct 47 million-year-old bird.

The latest research team — which also included scientists from the University of Texas at Austin, University of Akron, Peking University and the Beijing Museum of Natural History — decided to use the same procedures to closely examine a fossil of Anchiornis huxleyi, recently described in Liaoning Province, People's Republic of China. The area has been a gold mine for paleontologists and, among other things, provided abundant evidence confirming a once-controversial theory that modern birds are descendants of theropod dinosaurs.

The Yale team and Julia Clarke, an associate professor of paleontology at the University of Texas at Austin's Jackson School of Geosciences, worked closely with Gao Keqin of Peking University and Li Quanguo and Meng Qingjin of the Beijing Museum of Natural History to select, sample and evaluate the anatomy and feathering of Anchiornis huxleyi, important in its own right as a new feathered dinosaur. The team's effort was funded by a special grant from the National Geographic Society and by the National Science Foundation.

The team closely examined 29 feather samples from the dinosaur and did an exhaustive measurement and location of melanosomes within the feathers. The team then did a statistical analysis of how those melanosomes compared to the types of melanosomes known to create particular colors in living birds, using data compiled by Matt Shawkey and colleagues at the University of Akron. The analysis allowed scientists to discern with 90 percent certainty the colors of individual feathers and, therefore, the colorful patterns of an extinct animal.

The research adds significant weight to the idea that dinosaurs first evolved feathers not for flight but for some other purposes.

"This means a color-patterning function — for example, camouflage or display — must have had a key role in the early evolution of feathers in dinosaurs, and was just as important as evolving flight or improved aerodynamic function," Clarke said.

The new discoveries provide a wealth of insights into the compelling history of feather evolution in dinosaurs prior to the origin of modern birds. The study documents that color patterning within feathers and among feathers evolved earlier than previously believed. Further, these results indicate dinosaur feathers may have evolved for communication.

Friday, February 05, 2010 | 0 Comments

Bird migration becoming more hazardous

“Australia is the end-point of one of these migration routes, the busy East Asian-Australasian Flyway, which connects us with a dozen Asian countries,” Dr Fuller said.

“This amazing wildlife spectacle is under threat.

"Some species using the flyway have declined enormously over the past couple of decades, with millions of birds being lost.

"Two of the commonest species (great knots and eastern curlews) are currently being considered for admission to the red list of species threatened with global extinction because they have declined so fast and so dramatically.

“What has caused these declines is not clear. There has been considerable loss of wetlands in Australia, but these appear not to be dramatic enough to explain the declines in migratory shore birds.”

But, according to Dr Fuller, there is another, more worrying possible explanation for the declines. During their migrations, the birds stop at “refuelling” sites in estuaries around the Yellow Sea, but these estuaries are rapidly disappearing because of land reclamation projects as the region undergoes an economic boom, he says.

“One of the biggest projects is at Saemangeum, South Korea, where construction of a 33km seawall has converted 40,000 hectares of prime estuarine habitat in to dry land," Dr Fuller said.

"It is estimated that approximately 100,000 birds could have been lost as a result of this development alone because they no longer have a place to refuel on their migration.”

“Conserving migratory animals is extremely hard because they fly across international borders. Robust international policies are needed to ensure protection of the whole migration route, because the whole system is only as strong as its weakest point.”

However, there is hope. Australia had signed bilateral agreements with Japan, China and South Korea aimed at protecting habitats for migratory birds, Dr Fuller said.

Thursday, February 04, 2010 | 0 Comments

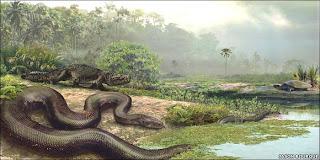

Ancient crocodile relative likely food source for Titanoboa

A 60-million-year-old relative of crocodiles described this week by University of Florida researchers in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology was likely a food source for Titanoboa, the largest snake the world has ever known. Working with scientists from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, paleontologists from the Florida Museum of Natural History on the UF campus found fossils of the new species of ancient crocodile in the Cerrejon Formation in northern Colombia. The site, one of the world's largest open-pit coal mines, also yielded skeletons of the giant, boa constrictor-like Titanoboa, which measured up to 45 feet long. The study is the first report of a fossil crocodyliform from the same site.

A 60-million-year-old relative of crocodiles described this week by University of Florida researchers in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology was likely a food source for Titanoboa, the largest snake the world has ever known. Working with scientists from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, paleontologists from the Florida Museum of Natural History on the UF campus found fossils of the new species of ancient crocodile in the Cerrejon Formation in northern Colombia. The site, one of the world's largest open-pit coal mines, also yielded skeletons of the giant, boa constrictor-like Titanoboa, which measured up to 45 feet long. The study is the first report of a fossil crocodyliform from the same site.Specimens used in the study show the new species, named Cerrejonisuchus improcerus, grew only 6 to 7 feet long, making it easy prey for Titanoboa. Its scientific name means small crocodile from Cerrejon.

The findings follow another study by researchers at UF and the Smithsonian providing the first reliable evidence of what Neotropical rainforests looked like 60 million years ago.

While Cerrejonisuchus is not directly related to modern crocodiles, it played an important role in the early evolution of South American rainforest ecosystems, said Jonathan Bloch, a Florida Museum vertebrate paleontologist and associate curator.

"Clearly this new fossil would have been part of the food-chain, both as predator and prey," said Bloch, who co-led the fossil-hunting expeditions to Cerrejon with Smithsonian paleobotanist Carlos Jaramillo. "Giant snakes today are known to eat crocodylians, and it is not much of a reach to say Cerrejonisuchus would have been a frequent meal for Titanoboa. Fossils of the two are often found side-by-side."

The concept of ancient crocodyliforms as snake food has its parallel in the modern world, as anacondas have been documented consuming caimans in the Amazon. Given the ancient reptile's size, it would have been no competition for Titanoboa, Hastings said.

Cerrejonisuchus improcerus is the smallest member of Dyrosauridae, a family of now-extinct crocodyliforms. Dyrosaurids typically grew to about 18 feet and had long tweezer-like snouts for eating fish. By contrast, the Cerrejon species had a much shorter snout, indicating a more generalized diet that likely included frogs, lizards, small snakes and possibly mammals.

"It seems that Cerrejonisuchus managed to tap into a feeding resource that wasn't useful to other larger crocodyliforms," Hastings said.

The study reveals an unexpected level of diversity among dyrosaurids, said Christopher A. Brochu, a paleontologist and associate professor in geosciences at the University of Iowa.

"This diversity is more evolutionarily complex than expected," said Brochu, who was not involved in the study. "A limited number of snout shapes evolved repeatedly in many groups of crocodyliforms, and it appears that the same is true for dyrosaurids. Certain head shapes arose in different dyrosaurid lineages independently."

Dyrosaurids split from the branch that eventually produced the modern families of alligators and crocodiles more than 100 million years ago. They survived the major extinction event that killed the dinosaurs but eventually went extinct about 45 million years ago. Most dyrosaurids have been found in Africa, but they occur throughout the world. Prior to this finding, only one other dyrosaurid skull from South America had been described.

Scientists previously believed dyrosaurids diversified in the Paleogene, the period of time following the mass extinction of dinosaurs, but this study reinforces the view that much of their diversity was in place before the mass extinction event, Brochu said. Somehow dyrosaurids survived the mass extinction intact while other marine reptile groups, such as mosasaurs and plesiosaurs, died out completely.

The crocodyliform's diminutive size came as a surprise, Hastings said, especially considering the giant reptiles that lived during the Late Cretaceous. The fossil record also points to the possibility of other types of ancient crocodyliforms inhabiting the same ecosystem. "In a lot of these tropical, diverse ecosystems in which crocodyliforms can thrive, you often see multiple snout types," he said. "They tend to start speciating into different groups."

Wednesday, February 03, 2010 | 0 Comments

DNA testing on 2,000-year-old bones in Italy reveal East Asian ancestry

"These preliminary isotopic and mtDNA data provide tantalizing evidence that some of the people who lived and died at Vagnari were foreigners, and that they may have come to Vagnari from beyond the borders of the Roman Empire," says Prowse. "This research addresses broader issues relating to globalization, human mobility, identity, and diversity in Roman Italy."

Based on her work in the region, she thinks the East Asian man, who lived sometime between the first to second centuries AD—the early Roman Empire—was a slave or worker on the site. His surviving grave goods consist of a single pot (which archaeologists used to date the burial). What's more, his burial was disturbed in antiquity and someone was buried on top of him.

Prowse's team cannot say how recently he, or his ancestors, left East Asia: he could have made the journey alone, or his East Asian genes might have come from a distant maternal ancestor. However, the oxygen isotope evidence indicates that he was definitely not born in Italy and likely came here from elsewhere in the Roman Empire.

During this era, Vagnari was an Imperial estate owned by the emperor in Rome and controlled by a local administrator. Workers were employed in industrial activities on the site, including iron smelting and tile production. These tiles were used for roofing buildings on the site and were also used as grave covers for the people buried in the cemetery. Fragmentary tiles found in and around Vagnari are marked "Gratus Caesaris", which translates into "slave of the emperor."

In addition to the mystery the find uncovers, Prowse sees the broader scientific impact for archaeologists, physical anthropologists, and classicists: The grave goods from this individual's burial gave no indication that he was foreign-born or of East Asian descent.

"This multi-faceted research demonstrates that human skeletal remains can provide another layer of evidence in conjunction with archaeological and historical information," says Prowse.

Tuesday, February 02, 2010 | 1 Comments

With climate change, birds are taking off for migration sooner; not reaching destinations earlier

Pied flycatchers are one of the best-studied migratory bird species in the world. With records going back more than 50 years, researchers have been able to investigate the birds' reaction to climate change over time. Pied flycatchers are also forest-dwelling, which makes them particularly interesting because of the strong seasonality in food dynamics in the forest.

"Forests are characterized by a short burst of insects rather early in spring," Both explained. "If the birds miss this insect peak for raising their chicks, they do not produce enough offspring to keep up their population sizes."

Like many migrants, pied flycatchers must tackle a rather remarkable and grueling trek each spring to reach their breeding sites. They spend their winters in Western Africa, anywhere from 5000 to 9000 kilometers from their breeding grounds across Europe and western Siberia. Their wintering grounds in Africa become progressively drier over the course of the season, and by the end of that dry spell, they somehow have to accumulate enough resources to fly about 2000 kilometers across the Sahara desert. The birds recover in Northern Africa before heading to their final destinations.

"Based on our calculations, they are covering the distance from Northern Africa to The Netherlands in about 6 days, and to central Sweden in about 12 days," Both said. Only a small fraction of birds make it through that harrowing journey. For those that do, "in some of the northern or eastern breeding grounds, the first birds often arrive when the breeding areas are still snow-covered. And these birds are strictly insectivorous—earlier arrival probably means death because there are not enough insects to be found." In The Netherlands, circumstances are better at arrival, he added, but the birds there get little or no chance to rest before breeding and nest building must begin. In most cases during the warm springs of the past decade, birds in The Netherlands have laid their first eggs 7 to 8 days after completing their journey.

Both's team found that the birds left their wintering grounds and made it all the way to Northern Africa 10 days earlier in the year in 2002 than they did in 1980. Still, they didn't arrive at their European breeding grounds any sooner.

The findings imply that "little should be expected in terms of an evolutionary response [to climate change]: any genetic variation in spring departure is likely to be masked by environmental constraints and not translated into earlier arrival," the researchers conclude. "More generally, because climate change often alters temperatures differently at different periods in the year, adaptation of life cycles in animals with a complex annual cycle is not likely to be solved by simple phenotypic or evolutionary responses toward earlier phenology. An adaptive evolutionary response most likely is needed on a whole suite of different traits simultaneously, and it remains to be seen whether evolution can alter species quickly enough to stop their decline."

Monday, February 01, 2010 | 0 Comments